Originally published on Brooking Institution's Brown Center Chalkboard, December 11, 2013

On December 3, scores were released from the 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a test given every three years to 15 year-olds around the globe. Shanghai led the world in all three subjects—math, science, and reading. But that ranking is misleading. Shanghai has a school system that excludes most migrant students, the children of families that have moved to the city from rural areas of China. And now for three years running, the OECD and PISA continue to promote a distorted picture of Shanghai’s school system by remaining silent on the plight of Chinese migrant children and what is one of the greatest human rights calamities of our time.

The numbers are staggering. There are an estimated 230 million migrants in China. [1] Approximately 5-6 million people have moved from rural areas to Shanghai since 2000. Imagine a population the size of Los Angeles and Houston combined relocating to a city that was already larger than New York City—and in only thirteen years! Shanghai’s population today is estimated at about 24 million people, with 13 million native residents and 11 million migrants. For the most part, the migrants are poor laborers who fill the factories driving China’s export-driven economic boom.

The exclusionary school enrollment practices are rooted in China’s hukou (pronounced “who-cow”) system. Although hukou dates back centuries, the current system was created by Mao Zedong’s regime in 1958 to control internal mobility in China. Every family in China was issued a rural hukou by its home village or urban hukou by its home city, a document best understood as part domestic passport and part municipal license.

The hukou controls access to municipal services. Migrants in China with rural hukous are barred from a host city’s services, in particular, social welfare programs, healthcare providers, and much of the school system. Hukous are transferred from generation to generation. The children of migrants, even if born in Shanghai, receive their parents’ rural hukou, which their children, too, will someday inherit no matter where they are born. As Kam Wing Chan, a Chinese migration and hukou expert at the University of Washington, puts it, “Under this system, some 700-800 million people are in effect treated as second class citizens, deprived of the opportunity to settle legally in cities and of access to most of the basic welfare and state-provided services enjoyed by regular urban residents.”

Many Chinese officials recognize that hukous are harshly discriminatory. But reforms have been slow in coming. For decades, children from families with rural hukous were simply barred from big city public schools, shunted into dramatically inferior schools built especially for migrants. In a fall 2013 essay, Eli Friedman of Cornell University describes the migrant schools he visited in Beijing:

“These schools are hidden from sight, far from the towering monoliths of the central business district and the solemn Stalinist facades of Tian’anmen. They are tucked into narrow alleys strewn with trash and populated by mangy street dogs, seemingly a world away from the ‘global’ part of the city. Most schools are in dilapidated single-story brick buildings, with no indoor plumbing or central heating. While the city’s public schools are all decked out in new multimedia appliances and computer labs, migrant schools often have only a single computer for the principal. Playgrounds in these schools hardly count as such — typically there’s nothing more than a potholed concrete slab that serves as a basketball court for hundreds of students at a time. In the very first school I visited, children were playing in a mound of crushed coal, subaltern Beijing’s equivalent of a sandbox.”

Theoretically, at least, the ban against Shanghai’s migrant children attending primary and middle schools (up to age 14) was lifted in 2008. For high schools (and the potential PISA population), Shanghai adopted a point system allowing some migrant children with highly educated parents or other high status characteristics to attend. That system went into effect July 1, 2013 so it is too early to gauge the impact of this very modest reform. And it obviously would have had no effect on Shanghai’s school population for PISA 2012.

The barriers to migrants attending Shanghai’s high schools remain almost insurmountable. High schools in Shanghai charge fees. Sometimes the fees are legal, but often in China, they are no more than bribes, as the Washington Post has reported. Students must take the national exam for college (gaokao) in the province that issued their hukou. An annual mass exodus of adolescents from city to countryside takes place, back to impoverished rural schools. At least there, migrant kids might have a shot at college admission. This phenomenon is unheard of anywhere else in the world; it’s as if a sorcerer snaps his fingers, and millions of urban teens suddenly disappear.

The toll on children and parents is staggering. Families are torn apart. Some migrant parents leave their children with relatives in villages when they initially move to cities in search of work. The All China Women’s Federation estimates 61 million children are “left behinds,” as they are known in the country. These children’s lives are marked by loneliness and despair. A recent book, Diaries of China’s Left Behind Children, poignantly describes their plight. The book caused a huge sensation in China.

Children who accompany their parents to the city but are then sent back to rural areas for high school fare no better than the left behinds. In 2012, a 15 year-old Shanghai student, Zhan Haite, went on the internet to protest that she, despite living in Shanghai since she was six years old, was barred from enrolling in a Shanghai high school. Why, she asked, should she be sent to Jiangxi province for high school, a rural area from which her parents had come but where she had never lived?

China, Shanghai, and OECD-PISA

In 2010, Andreas Schleicher of the OECD revealed that the 2009 PISA was conducted in 12 provinces in China. The data from mainland provinces other than Shanghai have never been released, and OECD’s list of participants in the 2009 PISA continues to omit them. A Chinese website leaked purported scores from other provinces, but the scores have never been confirmed by PISA officials in Paris.

This shroud of secrecy is peculiar in international assessment. Now the world has new data from the 2012 PISA. The OECD has not disclosed if other Chinese provinces secretly took part in the 2012 assessment. Nor have PISA officials disclosed who selected the provinces that participated. Did the Chinese government pick the provinces? Does the Chinese government decide which scores will be released? In 2012, the BBC reported that the Chinese government did not “allow” the OECD to publish PISA 2009 data on provinces other than Shanghai. There is a lack of transparency surrounding PISA’s relationship with China.

Shanghai is portrayed as a paragon of equity in PISA publications. A 2010 OECD publication, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education, highlights model systems that the world should emulate. Shanghai is singled out for praise. One section on Shanghai is entitled, “Ahead of the pack in universal education.” The city is described as an “education hub,” and the only discussion that even remotely touches upon migrants is the following:

“Graduates from Shanghai’s institutions are allowed to stay and work in Shanghai, regardless of their places of origin. For that reason, many ’education migrants now move to Shanghai mainly to educate their children.” [2]

That description is surreal. PISA’s blindness to what is really going on in Shanghai was also evident in the official release of PISA’s latest scores. The 2012 data appear in volumes organized by themes. Volume II is entitled, PISA 2012 Results: Excellence through Equity, Giving Every Student the Chance to Succeed. Shanghai is named as one jurisdiction where schools “achieve high mathematics performance without introducing greater inequities in education outcomes (p. 28)” and one with “above average socio-economic diversity (p. 30).” In the 336 pages of this publication on equity, the word “migrant” appears only once, in a discussion of Mexico. The word “hukou” does not appear at all.

Is it possible that PISA officials are simply unaware of the hukou system and the media coverage cited above? That’s doubtful, but even if it were the case, PISA’s own data shout out that something is wrong with Shanghai’s enrollment numbers. PISA reports that 90,796 of Shanghai’s 15 year-olds are enrolled in school in grade 7 or above, out of a total population of 108,056 15 year-olds, producing an enrollment rate of about 84%. That’s comparable to other PISA participants. [3] Shanghai appears as inclusive as any other PISA participant.

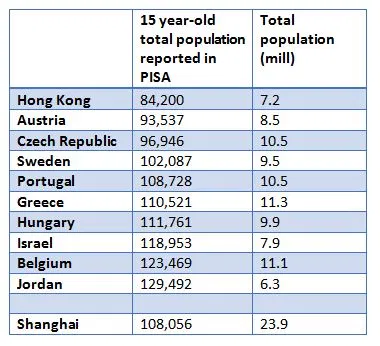

The denominator in that ratio, total population of 15 year-olds, is suspicious. Examine the statistics in Table 1, the ten PISA participants most similar to Shanghai’s total numbers of 15 year-olds. As shown in the first column, the 15 year-old populations range from 84,200 in Hong Kong to 129,492 in Jordan. The second column shows the participating jurisdictions’ total populations—adults, children, everyone. They range from 6.3 to 11.3 million. How is it that Shanghai, with a population two to four times that of these ten countries, yields a similar number of 15 year-olds? A back of the envelope calculation suggests that a jurisdiction with 24 million people should yield a minimum of 230,000 15 year-olds. The missing population in Shanghai exceeds the recognized one. Where did all of Shanghai’s 15 year-olds go?

Table 1. Shanghai and Ten Other PISA Participants’ Population Statistics

The most reasonable explanation is that migrant children are not counted in Shanghai’s figures. But let’s consider other explanations. Perhaps China’s “one child” policy has been so effective that Shanghai has fewer children than other places. No, that doesn’t make sense. The World Bank estimates that children ages 0-14 constitute 18% of China’s overall population, which is comparable to most of the nations in Table 1. [5] Don’t forget that for several years, European families have practiced their own “one child” policy without any guidance from government.

Perhaps Shanghai counted migrant children earlier in their school careers, but then, as indicated from the numerous accounts above, the children leave the city during the transition to high school. That is probably closer to the truth, but the numbers still do not square with other Shanghai data reported in PISA publications—for example, that Shanghai’s enrollment rate at the age of compulsory education (primary and junior secondary) is 99.9% and that 97% attend senior secondary school. These figures can only be reconciled if migrant children, children without a Shanghai hukou, are never counted in school population statistics. That is stunning. Nevertheless, PISA praises Shanghai for achieving “universal primary and junior secondary education” and “almost universal senior secondary education.” [6]

Also consider that the 108,056 figure reported in 2012 (and shown in Table 1) is a decline from the 112,000 total number of 15 year-olds reported in PISA 2009. How can that possibly happen in a city that has been adding approximately one-half million people a year since 2000? If Shanghai added 1.5 million people from 2009-2012, how could the number of 15 year-olds decline? Again, it can only be because migrants aren’t being counted. Shanghai’s non-migrant population (those holding a Shanghai hukou) is indeed falling, and has been falling steadily for more than 15 years. Shanghai’s population growth is entirely due to migrants. The decline in the number of 15 year-olds from 2009-2012 alone should have alerted PISA officials that something was amiss with the enrollment data coming out of Shanghai.

The only reasonable conclusion is this: officials in Shanghai are only counting children with Shanghai hukous as its population of 15 year-olds, about 108,000. And the OECD is accepting those numbers. It is as if the other children, numbering 120,000 or more, do not exist. This is not a sampling problem. PISA can sample all it wants from the official population. Migrant children have been filtered out. Professor Chan of Washington agrees with this hypothesis, saying in an email to me: “By the time PISA is given at age 15, almost all migrant children have been purged from the public schools. The data are clear.”

What Now?

As a researcher who studies student achievement, I use PISA data. That requires trust and confidence in the integrity of the assessment. I can be confident, for example, that the scores from Portugal are from a representative sample of all 15 year-olds in Portuguese schools. I have no such faith in PISA scores from China. PISA-OECD has been silent about its special arrangement with China. All of the data from 2009 still have not been released. The data from Shanghai apparently only represent the privileged subset of 15 year-olds who hold Shanghai hukous. I don’t know for sure. In the four volumes of data on PISA 2012, neither hukous nor the migrant children of China are discussed. Not a word. Not a peep.

PISA officials are not shy about offering policy advice to countries, especially policies that the OECD believes will promote equity. Delaying tracking and ability grouping, reforming policies governing immigration, distributing resources so that schools with less get more, and expanding early childhood education—all have been promoted as equity-based policies. But not a word about reforming hukou. Not a word on a discriminatory policy affecting the education of millions of Chinese children. Not a word on the human rights story of migrant families in China and the human suffering that they must endure.

TES, a European magazine, reported on December 6 that China has decided to participate as a nation in the next round of PISA tests in 2015. Let’s hope that the PISA Governing Board (PGB) takes strong, effective action to clean up the mess surrounding PISA’s testing in China by then.

[1] The official census put the number at 230 million in 2010.

[2] OECD, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education, p. 91. (http://www.oecd.org/pisa/46623978.pdf)

[3] Enrollment rates are adjusted for exclusions to produce a weighted number of participating students.

[4] PISA data on 15 year olds from Table A2.1, “PISA Target Populations and Samples,” What Makes Schools Successful? Resources, Policies, and Practices-Volume IV, p. 211. General population data from The World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL).

[5] http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.0014.TO.ZS/countries?display=default

[6] OECD, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education, p. 91. (http://www.oecd.org/pisa/46623978.pdf)